Background:

Despite what others would say, there is no denying that the Bible speaks of predestination. From the Old Testament to the New, predestination is demonstrated through God’s selection of particular groups of people for His purposes. We can see this in the life of the Israelites. God chose specific individuals within that group to carry out His mission (Abraham, Issac, Jacob, Moses, etc.). It is completely God’s prerogative to make His choices, not based on merit or foreshadowing, but solely on God’s volition.  For instance, when God chose Abraham to be the father of many nations (Gen 12:1-3), when God chose Israel to be His representative people (Deut 7:6-8), or when God chose the Gentiles to be ingrafted into the people of God (Rom 9:24-26). These are all examples of God selecting certain groups or individuals for His purpose in the Old Testament. There is no denying that the selections God made were His own. Why, of all people on earth, did God select the Israelites to be His representatives? Were they different and special in some sense? Are they better people than others? Most likely not, and they were probably ordinary people living their lives, yet God, in His mercy and grace, decided to reveal His identity through the people of Israel. Only in the New Testament was God’s image truly revealed in the person of Jesus Christ.

For instance, when God chose Abraham to be the father of many nations (Gen 12:1-3), when God chose Israel to be His representative people (Deut 7:6-8), or when God chose the Gentiles to be ingrafted into the people of God (Rom 9:24-26). These are all examples of God selecting certain groups or individuals for His purpose in the Old Testament. There is no denying that the selections God made were His own. Why, of all people on earth, did God select the Israelites to be His representatives? Were they different and special in some sense? Are they better people than others? Most likely not, and they were probably ordinary people living their lives, yet God, in His mercy and grace, decided to reveal His identity through the people of Israel. Only in the New Testament was God’s image truly revealed in the person of Jesus Christ.

Not only is God’s choices displayed in the Old Testament, we see it in the New Testament when Jesus calls the twelve disciples and clarifies to them that He chose them (John 15:16). We also find God’s divine initiative written in the epistles of Paul and the disciples (Eph 1:4-5; Rom 9:11-16; John 6:37, 44; 2 Thes 2:13; James 2:5; 1 Cor 1:27-29).  The New Testament speaks of the mystery of God’s revelation in the Old Testament. God came down in the form of Christ and carved a path of salvation and righteousness. He made it possible for sinners to enter the Kingdom of Heaven. It is only through Christ that anyone can be saved. But that option was not left open for “anyone.” That is the difference between predestinarians and free-willers. The “L” in Limited Atonement is what hinders many people from understanding the acronym T.U.L.I.P., which originates from Calvinism. We will cover the meaning of this later on, but for now, the conflict of who is saved and who is not saved is what causes consternation to many. The New Testament believers of their time must have struggled with this very question as well. Why else would Paul and the disciples write so fervently and often about God’s election and predestination? These questions must have lingered in the minds of the believers in the first century. We still struggle with it today in the twenty-first century.

The New Testament speaks of the mystery of God’s revelation in the Old Testament. God came down in the form of Christ and carved a path of salvation and righteousness. He made it possible for sinners to enter the Kingdom of Heaven. It is only through Christ that anyone can be saved. But that option was not left open for “anyone.” That is the difference between predestinarians and free-willers. The “L” in Limited Atonement is what hinders many people from understanding the acronym T.U.L.I.P., which originates from Calvinism. We will cover the meaning of this later on, but for now, the conflict of who is saved and who is not saved is what causes consternation to many. The New Testament believers of their time must have struggled with this very question as well. Why else would Paul and the disciples write so fervently and often about God’s election and predestination? These questions must have lingered in the minds of the believers in the first century. We still struggle with it today in the twenty-first century.

If God does know all things and chooses to allow certain evils to occur, how do we rationalize this? If God allows evil to occur, does that make Him evil or the originator of evil? The Bible teaches that only God is good (Mark 10:18). Since God is good, how can He allow evil to continue? This question beats at the heart of predestination. If God is sovereign to the point of absolute control, then life is meaningless because we are not the arbiters of our lives. So, to believe in predestination goes further than just election. It means accepting other logical chains that must be addressed, such as why we evangelize and whether we are all robots. The historical church dealt with similar questions as it struggled with God’s sovereign will. Does God’s will override ours, and if so, when and how often?

If God does know all things and chooses to allow certain evils to occur, how do we rationalize this? If God allows evil to occur, does that make Him evil or the originator of evil? The Bible teaches that only God is good (Mark 10:18). Since God is good, how can He allow evil to continue? This question beats at the heart of predestination. If God is sovereign to the point of absolute control, then life is meaningless because we are not the arbiters of our lives. So, to believe in predestination goes further than just election. It means accepting other logical chains that must be addressed, such as why we evangelize and whether we are all robots. The historical church dealt with similar questions as it struggled with God’s sovereign will. Does God’s will override ours, and if so, when and how often?

If God were to base His decisions on what creatures would do, and if we were to try to preserve His goodness and holiness (as the free-willers do), then we must conclude that God would be unaware of future events, which contradicts His omniscience.  If God knows all things and all events, and evil actions occur, then God must have either allowed them to happen or purposefully caused them to happen. That would make Him the originator of evil, which makes God not good. Do you see the merry-go-round ride as an attempt to uphold the free will view or the predestination view? One question leads to another and another and another. It keeps flipping back and forth, trying to reconcile Scripture with various theories. It is a dizzying activity that eventually drove me to want to give up the whole thing, or surrender to it. This is the reason why the Church of Christ was divided into multiple denominations, along with other doctrinal differences in interpretation.

If God knows all things and all events, and evil actions occur, then God must have either allowed them to happen or purposefully caused them to happen. That would make Him the originator of evil, which makes God not good. Do you see the merry-go-round ride as an attempt to uphold the free will view or the predestination view? One question leads to another and another and another. It keeps flipping back and forth, trying to reconcile Scripture with various theories. It is a dizzying activity that eventually drove me to want to give up the whole thing, or surrender to it. This is the reason why the Church of Christ was divided into multiple denominations, along with other doctrinal differences in interpretation.

In my journey from following free will theology, I could not find a satisfactory answer that helped me find peace. I always felt I had to be on the ready and alert to do my best. Nothing wrong with that, and we should strive to do our best. However, a spiritual life focused on works will lead to a confused soteriology (Study of salvation).  No satisfactory answers were given from the free will side that helped me to worship and glorify God. All I ended up doing was trying to live better, stop my sins, and spread the Word. It became work-based salvation that crept up behind me and confused my understanding of grace. The moment our works get involved in the salvific process of God’s completed works, then we have turned Christianity into something else. Works are essential and must always follow grace as a response, but never precede it, and never succeed it. Our works do not count or contribute to Christ’s finished work. Our works are a gratuitous response to God’s mercy and grace, which He first showed us. Our works are for His glory.

No satisfactory answers were given from the free will side that helped me to worship and glorify God. All I ended up doing was trying to live better, stop my sins, and spread the Word. It became work-based salvation that crept up behind me and confused my understanding of grace. The moment our works get involved in the salvific process of God’s completed works, then we have turned Christianity into something else. Works are essential and must always follow grace as a response, but never precede it, and never succeed it. Our works do not count or contribute to Christ’s finished work. Our works are a gratuitous response to God’s mercy and grace, which He first showed us. Our works are for His glory.

To take the argument a little further, in Isaiah, we read that God knows all things “from the beginning and from ancient times” (Isaiah 46:9-10). So, if God knows all things, bases His decision on our choices, and lets us continue in our bad decisions knowing we will continue in them, then God cannot be good, is what the free-willer would say. He would be intentionally letting people fall.  However, God’s purposes are good, always. God is incapable of making a bad decision because He is God. God is not a creature that we need to keep in check and ensure He is doing the right thing. That would make us gods. No, God is independent of all other causes and relations. God never responds but only initiates. A response occurs when the one answering is unaware of the reason. God does not answer; He acts and initiates. This means all things happen according to God’s will and purpose. The Calvinist would agree that God’s intent is for His glory and the good of all. God does not have evil, nor can He commit evil. That is like saying a dog can become a cat one day. It goes against its nature and being. God cannot be anything other than God. No matter what you think, nor what anyone may imagine, God is who He is, and our perception of Him is always skewed and warped to some degree due to sin. We do not have a perfect image of God, except through Jesus Christ. He is the perfect representation and image we can see and know. He is Emanual, God with us (Isaiah 7:14).

However, God’s purposes are good, always. God is incapable of making a bad decision because He is God. God is not a creature that we need to keep in check and ensure He is doing the right thing. That would make us gods. No, God is independent of all other causes and relations. God never responds but only initiates. A response occurs when the one answering is unaware of the reason. God does not answer; He acts and initiates. This means all things happen according to God’s will and purpose. The Calvinist would agree that God’s intent is for His glory and the good of all. God does not have evil, nor can He commit evil. That is like saying a dog can become a cat one day. It goes against its nature and being. God cannot be anything other than God. No matter what you think, nor what anyone may imagine, God is who He is, and our perception of Him is always skewed and warped to some degree due to sin. We do not have a perfect image of God, except through Jesus Christ. He is the perfect representation and image we can see and know. He is Emanual, God with us (Isaiah 7:14).

The Bible shows God making the decisions based on His own authority, not our future choices. Nowhere does it say that God chose a person or people because He knew what they would do in the future. I will cover this more later, but the Bible is quite evident in its teachings. God is independent of our will and chooses based on His own authority. The two main verses that support predestination are Romans 8:29-30 – “Those whom He foreknew, He also predestined…”, and Ephesians 1:4-5 – “He chose us in Him before the foundation of the world…”.

Examining church history and its beliefs in predestination, the Calvinists argue that God chooses those who are to be saved based on His foreknowledge. The Arminian would also agree. However, both understandings of foreknowledge differ. For the Calvinist, foreknowledge refers to God not only knowing and seeing future events and outcomes, but also decreeing all things to happen. Armenians believe God’s foreknowledge is God looking into the future to see what we would do, and basing His choices on our decisions, not wanting to violate our freedom. Both views are an expansion of the previous similar views held by Augustine and Pelagius of the 4th century. All modern views are branches of these two root positions.

Below is a simple chart of the differing views of this important topic:

| Era/Thinker | Predestination View | Free Will View |

| Bible (1st C.) | God elects (Rom 8, Eph 1); His will prevails | Humans are responsible; moral choices matter |

| Augustine (400s) | God’s grace is necessary and decisive; unconditional election | Free will exists, but is bound by sin without grace |

| Pelagius (400s) | Humans are born innocent; they can choose good without divine help | Complete human moral freedom; grace is helpful but not essential |

| Calvin (1500s) | Double predestination: God sovereignly chooses salvation and reprobation | Will is bound to sin; no free will in salvation |

| Arminius (1600s) | Election based on foreseen faith; grace enables choice | Humans can accept or reject grace, synergistic cooperation |

| Modern | Varied: Calvinism, Arminianism, Molinism, Open Theism | Will debated in theology, neuroscience, and philosophy |

Calvinism has its roots in Augustinian views, while Arminius’ view draws on Pelagius’ teachings. The doctrine gradually evolved into what it is today. Many may say; Why divide the Church over such a silly doctrine? I would agree that this doctrine should not cause division. However, it does touch on the very fabric of our understanding of God and who God is. Augustine’s doctrine of Grace should not be for those who are starting out or early in the faith.  This and many other doctrines can confuse the young believer, but they are necessary for growth and a deeper understanding of your faith. You don’t have to deal with it now if it upsets you. However, you will find yourself coming back to the question of God’s sovereignty and your responsibility. It is unavoidable. Also, predestination should not be taught to children or new believers, nor should it be used for evangelism. Not all doctrines apply to evangelism, especially when it concerns Calvin’s view of double predestination. I don’t believe anyone would come to Christ if that message were given out in a tract. No, God’s grace is what should be explained in evangelism. Predestination and free will doctrines are typically reserved for those who have been in the faith for a while, understand the basic teachings of Christianity, and are ready to stretch and flex their faith muscles to grow. The road will not be easy, and many have fallen from it, but in the end, God will always come to fruition.

This and many other doctrines can confuse the young believer, but they are necessary for growth and a deeper understanding of your faith. You don’t have to deal with it now if it upsets you. However, you will find yourself coming back to the question of God’s sovereignty and your responsibility. It is unavoidable. Also, predestination should not be taught to children or new believers, nor should it be used for evangelism. Not all doctrines apply to evangelism, especially when it concerns Calvin’s view of double predestination. I don’t believe anyone would come to Christ if that message were given out in a tract. No, God’s grace is what should be explained in evangelism. Predestination and free will doctrines are typically reserved for those who have been in the faith for a while, understand the basic teachings of Christianity, and are ready to stretch and flex their faith muscles to grow. The road will not be easy, and many have fallen from it, but in the end, God will always come to fruition.

Key Figures & Events

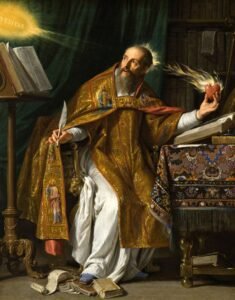

In the 4th-5th century (354–430 AD), St. Augustine of Hippo was a bishop, theologian, and philosopher who wrote extensively about predestination, which caused considerable controversy. He was deeply influenced by Manichaeism and later Neoplatonism, and subsequently developed his theology after his conversion at the age of 31. He taught that human sin was binding due to the Fall (also known as Original Sin) and that only God can save (the Doctrines of Grace). It is by God’s grace that He elects who should be saved, not based on human merits. Augustine wrote to refute Pelagius’ belief that humankind is inherently good and retains complete free will. To Pelagius, God’s election is based on what He foresees in human merits (Hippo 2016).

In the 4th-5th century (354–430 AD), St. Augustine of Hippo was a bishop, theologian, and philosopher who wrote extensively about predestination, which caused considerable controversy. He was deeply influenced by Manichaeism and later Neoplatonism, and subsequently developed his theology after his conversion at the age of 31. He taught that human sin was binding due to the Fall (also known as Original Sin) and that only God can save (the Doctrines of Grace). It is by God’s grace that He elects who should be saved, not based on human merits. Augustine wrote to refute Pelagius’ belief that humankind is inherently good and retains complete free will. To Pelagius, God’s election is based on what He foresees in human merits (Hippo 2016).

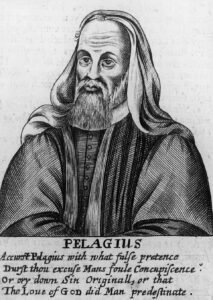

Pelagius (c. 360-418 AD) was a theologian and British monk who sparked debates and caused controversies in early Christianity. He taught that humans possess moral ability and free will, and that grace is helpful but not necessary. Pelagius also believed that Adam’s original sin did not corrupt human nature, and humans are morally born neutral. Baptism was not needed, but recommended for a commitment to moral living (Ferguson 1978).

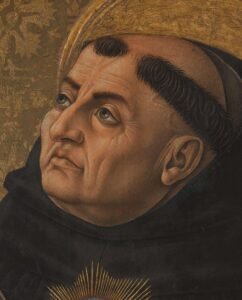

During the Middle Ages, Thomas Aquinas, a Dominican friar, philosopher, Catholic priest, and theologian, was well-known for integrating Aristotle’s philosophy with Christian Theology. Aquinas taught that God’s grace and human cooperation are essential to salvation (synergism). Grace is from God, but man must cooperate with that grace (belief with penance). Human effort is required for salvation (Thomas and Thomas 2000).

During the Middle Ages, Thomas Aquinas, a Dominican friar, philosopher, Catholic priest, and theologian, was well-known for integrating Aristotle’s philosophy with Christian Theology. Aquinas taught that God’s grace and human cooperation are essential to salvation (synergism). Grace is from God, but man must cooperate with that grace (belief with penance). Human effort is required for salvation (Thomas and Thomas 2000).

John Calvin, during the Reformation, further developed Augustine’s theology in his writings on the doctrine of double predestination. He stated that God elects some unto salvation, while others unto damnation. No one goes without being elected. Human effort and choices are removed. Martin Luther also taught of God’s sovereignty and humans’ captivity to sin, which aligns with Calvin’s teachings (Calvin 2008).

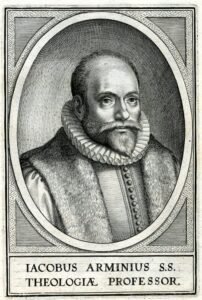

Jacobus Arminius, 1560–1609, rejected the Reformation’s teaching on predestination and instructed that God’s election is based on conditional merits, as well as resistible grace based on God’s foreknowledge. In other words, God elects people to salvation based on their decision to follow Christ or not. Grace is resistible and can be lost (Arminius et al. 1991).

Jacobus Arminius, 1560–1609, rejected the Reformation’s teaching on predestination and instructed that God’s election is based on conditional merits, as well as resistible grace based on God’s foreknowledge. In other words, God elects people to salvation based on their decision to follow Christ or not. Grace is resistible and can be lost (Arminius et al. 1991).

The Synod of Dort, held in 1618-1619, was the central council of the church convened by the Dutch Reformers in the Netherlands. They settled the dispute between the Arminians and Calvinists. The Synod rejected Arminianism and its Five Articles of the Remonstrants and affirmed Calvin’s Five Points TULIP. The synod confirmed the Canons of Dort, which supported the Reformed Confessions of the 16th and 17th centuries (Olson 2009).

The Synod of Dort, held in 1618-1619, was the central council of the church convened by the Dutch Reformers in the Netherlands. They settled the dispute between the Arminians and Calvinists. The Synod rejected Arminianism and its Five Articles of the Remonstrants and affirmed Calvin’s Five Points TULIP. The synod confirmed the Canons of Dort, which supported the Reformed Confessions of the 16th and 17th centuries (Olson 2009).

The Christian Church faced numerous challenges and attacks, not only from the outside pagan world, but also from internal conflicts within the body of believers. It can be difficult and taxing on some believers as they don’t see the need to take things so seriously.  Most believers would be content to simply live day by day, loving the Lord and serving Him. That would be wonderful and highly recommended…in heaven. While we still reside on earth, we were given a task by our Lord to take the Gospel to the ends of the earth. Taking the Gospel means living the Gospel, which requires learning the Gospel. How are we to take the Word of truth to the world if we don’t fully understand it ourselves? We have an obligation and duty to learn these doctrines and truths, even though they may be unpleasant to hear or difficult to understand. God never calls and converts someone without plans to use them to produce the fruits of the Spirit. God’s intent is for growth in every way. We are to grow up unto maturity to be ready and able to defend the faith and serve the Lord with our talents.

Most believers would be content to simply live day by day, loving the Lord and serving Him. That would be wonderful and highly recommended…in heaven. While we still reside on earth, we were given a task by our Lord to take the Gospel to the ends of the earth. Taking the Gospel means living the Gospel, which requires learning the Gospel. How are we to take the Word of truth to the world if we don’t fully understand it ourselves? We have an obligation and duty to learn these doctrines and truths, even though they may be unpleasant to hear or difficult to understand. God never calls and converts someone without plans to use them to produce the fruits of the Spirit. God’s intent is for growth in every way. We are to grow up unto maturity to be ready and able to defend the faith and serve the Lord with our talents.

We have examined the history and background of the two primary views regarding God’s sovereignty and human autonomy. The debate roots back to the 4th century with Pelagius and Augustine battling over the doctrine of predestination and the free will of man. Those views developed into the two main branches of Calvinism versus Arminianism. From there, the church has divided over various issues relating to translations and interpretations of central doctrines. We have multiple denominations today, including Baptists, Lutherans, and Calvinists, among others.

In the following article, I will discuss why I disagree with free will theology and what the serious consequences of getting this doctrine wrong entail. I would like to disclose that the Church has been debating this doctrine for many years, and I don’t intend to convert or change anyone’s mind about their beliefs. I would like to raise a few questions for those who believe in free will, as these were questions I’ve struggled with that’ve yet to be answered. I leave room for the possibility that my view might be wrong, but to sway me away from predestination, these questions must be addressed.

In the following article, I will discuss why I disagree with free will theology and what the serious consequences of getting this doctrine wrong entail. I would like to disclose that the Church has been debating this doctrine for many years, and I don’t intend to convert or change anyone’s mind about their beliefs. I would like to raise a few questions for those who believe in free will, as these were questions I’ve struggled with that’ve yet to be answered. I leave room for the possibility that my view might be wrong, but to sway me away from predestination, these questions must be addressed.

Bibliography:

Calvin, Jean. 2008. Institutes of the Christian Religion. Peabody, Mass: Hendrickson Publishers.

Olson, Roger E. 2009. Arminian Theology: Myths and Realities. Westmont: InterVarsity Press.Thomas, and Thomas. 2000. St. Thomas Aquinas Summa Theologica: Complete English Edition in Five Volumes. Reprint. Notre Dame, Ind: Christian Classics.