In a world that constantly tells us to “just be nice” and “love everybody,” talking about doctrine—or firm beliefs—can feel awkward. But what if I told you that your beliefs aren’t just dry rules; they are the absolute core of what you believe and why you live the way you do?

The research is clear: Doctrine, which is the organized teaching of the truths in the Bible, acts like a defining fence. It brings those who agree close together, but it inevitably separates them from those who don’t. And that’s okay. Sometimes, division is necessary to protect the truth.

Beliefs Always Lead to Boundaries

You see this principle everywhere, not just in religion. Think of the Constitution in a democracy. It defines what the country is and is not. Any group that rejects the foundational principles of that document is, by definition, outside that democratic framework.

In Christianity, the stakes are eternal. Historically, the Church had to draw lines to survive:

- Who is Jesus? (The Ancient Problem): The earliest Christians didn’t argue over worship songs; they argued over the nature of Christ (Christology). When groups like the Arians said Jesus was a created superhero, not God Himself, the Church had to define Jesus as fully God and fully human. If they hadn’t, the Gospel (salvation relies on God himself saving us) would have collapsed. This split the Church, but it saved the message.

How are we Saved? (The Reformation Problem): The Reformers (like Luther) didn’t just want a new church structure; they had a profound doctrinal disagreement over salvation. Was it by faith alone, or faith plus works? When they declared it was “by grace through faith alone,” they were necessarily separated from the existing Catholic Church. This was a painful split, but it secured the core truth of the Gospel.

How are we Saved? (The Reformation Problem): The Reformers (like Luther) didn’t just want a new church structure; they had a profound doctrinal disagreement over salvation. Was it by faith alone, or faith plus works? When they declared it was “by grace through faith alone,” they were necessarily separated from the existing Catholic Church. This was a painful split, but it secured the core truth of the Gospel.- Does Scripture Hold Authority? (The Modern Problem): In the 19th and 20th centuries, conflicts arose when some religious leaders started viewing the Bible as merely a human book containing errors. Scholars like J. Gresham Machen argued that to partner with those who denied the Bible’s authority was to participate in the error itself. He correctly saw that “Fellowship with known and vital error is participation in sin.”

The Freedom of Firm Boundaries

We’re often taught that division is the greatest sin. But division is only bad if it’s over something small, like paint colors or style of music.

The crucial question is who is doing the dividing?

The crucial question is who is doing the dividing?

- The Error Divides: When someone introduces a belief that fundamentally changes the core Gospel message (like denying Christ’s deity or the resurrection), they are the one who has left the historic faith. They cause the split.

- The Truth Defines: The person or group standing firm on the established, biblical faith is simply holding the line. Their faithfulness reveals the separation the error already created.

We need to learn the difference between First-Rank Doctrines (like the Trinity, Christ’s resurrection, salvation by grace—which are non-negotiable) and Second- or Third-Rank Doctrines (like specific end-times timelines or baptism modes—which should allow for charity and unity).

When it comes to the fundamentals, standing firm is not unloving; it’s the most loving thing you can do for the Church and for those who need the true Gospel.

The Ultimate Reason to Learn True Doctrine

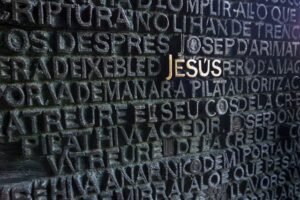

So why should you care about ancient debates and dusty doctrines? Because doctrine isn’t just information; it’s the map to the real Jesus.

So why should you care about ancient debates and dusty doctrines? Because doctrine isn’t just information; it’s the map to the real Jesus.

Every single one of those historic doctrinal fights—from the nature of the Holy Spirit to the means of salvation—was ultimately about protecting the true identity of God and the true work of Christ.If you don’t learn true doctrine, you won’t know the true Christ. You’ll be vulnerable to a faith that invents a god in your own image—a god who is too weak to save, too distant to care, or too soft to judge.

Here is a bibliography for the blog article, drawing upon the historical and theological sources cited or referenced in the initial query you provided. I’ve used a standard academic style (Chicago Manual of Style – Notes and Bibliography) for clarity.

Bibliography

Primary Sources and Classic Texts

- Bonhoeffer, Dietrich. Life Together. Translated by John W. Doberstein. New York: Harper & Row, 1954. (Referenced in the initial discussion about Bonhoeffer and practical theology, and useful for the “unity” discussion).

- Calvin, John. Institutes of the Christian Religion. Edited by John T. McNeill and translated by Ford Lewis Battles. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 1960. (Referenced as a source for foundational Reformed doctrine and piety).

- Machen, J. Gresham. Christianity and Liberalism. New York: Macmillan Company, 1923. (Source for the quote on fellowship with error and separation during the Fundamentalist-Liberal controversy).

- Wesley, John, Charles, and George Whitefield. Letters and writings concerning their doctrinal dispute (Arminianism vs. Calvinism). (Source for the conflict and the lamented division among Methodists).

- Westminster Assembly. The Westminster Confession of Faith and The Westminster Larger and Shorter Catechisms. (Referenced as foundational documents for Reformed theology and practical divinity).

Historical and Secondary Sources

- Hanson, R. P. C. The Search for the Christian Doctrine of God: The Arian Controversy 318–381. Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1988. (Context for the Arian controversy and the definition of the Trinity).

- Kelly, J. N. D. Early Christian Doctrines. Rev. ed. San Francisco: HarperCollins, 1978. (General context for Christological and Trinitarian controversies and definitions).

- Macleod, Donald. A Faith to Live By: Understanding Christian Doctrine. Fearn, Ross-shire, UK: Christian Focus Publications, 1998. (Discusses the purpose and necessity of doctrine for spiritual health).

- Olson, Roger E. The Story of Christian Theology: Twenty Centuries of Tradition & Reform. Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 1999. (General historical context for major doctrinal disputes, including the Filioque and the Reformation).

- Ryrie, Charles C. Basic Theology: A Popular Systematic Guide to Understanding Biblical Truth. Chicago: Moody Publishers, 11999. (Context for dispensationalism and the concept of a hierarchy of truths).

- Strauss, Mark L. Four Views on the Historical Adam. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2013. (Example of contemporary doctrinal debates over biblical interpretation and the “literal method”).

Theological Concepts and Frameworks

- Christology (The doctrine of the person of Christ and the definitions established at the Council of Chalcedon in 451 AD).

- Soteriology (The doctrine of salvation, encompassing debates over grace, faith, and works).

- Trinity (The doctrine of God existing as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit).

- Filioque Clause (Latin for “and the Son,” the controversial addition to the Nicene Creed).

How are we Saved? (The Reformation Problem): The Reformers (like Luther) didn’t just want a new church structure; they had a profound doctrinal disagreement over salvation. Was it by faith alone, or faith plus works? When they declared it was “by grace through faith alone,” they were necessarily separated from the existing Catholic Church. This was a painful split, but it secured the core truth of the Gospel.

How are we Saved? (The Reformation Problem): The Reformers (like Luther) didn’t just want a new church structure; they had a profound doctrinal disagreement over salvation. Was it by faith alone, or faith plus works? When they declared it was “by grace through faith alone,” they were necessarily separated from the existing Catholic Church. This was a painful split, but it secured the core truth of the Gospel.